I found myself tracking with Wilson-Hartgrove throughout this entire chapter until the very end when he writes,

But if pledging our allegiance is a way of saying who we are and where we’re going…we’ve got to say that our primary commitment is to the church (73).

No, not the church…Jesus! My primary commitment is to Jesus. Like the hymn sings, “The church’s one foundation is Jesus Christ our Lord.”—not herself! He goes on to say that our churches must then get serious about their membership (73); I totally disagree. Our churches need to get serious about loving God and loving God’s people (he did say this earlier). I readily understand and adopt his point that our ecclesial communities need to be more than just another event to attend in a suburban lifestyle that is already jammed full with too many events. But the church is not going to be legit with such a subversive message (that it is a way of life and not an activity) if it is about membership and loyalty to community over allegiance to Jesus and the kingdom of God.

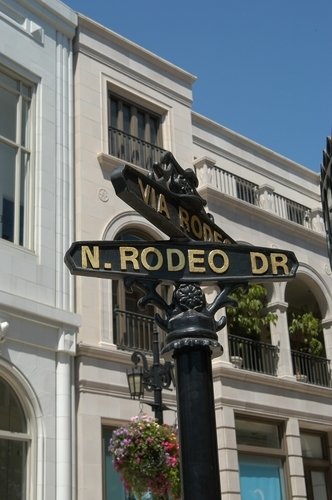

The discussion that Wilson-Hartgrove begins on page 80 is the piece in this puzzle that moves me the most. Moving into places that the Empire has rejected seems to me to not only be what Jesus modeled in who he spoke to and ate with, but even more realized in the fact that our allegiance is found in the Kingdom of God, as it was brought about by Jesus (which is why I cannot pledge my allegiance to the church). The poor, the mentally ill, the imprisoned, the handicap, the hungry, the ugly, the non-white, the immigrant, etc. live in areas of America that Capitol Hill, Wall Street, Madison Avenue, Rodeo Drive, and the Magnificent Mile do not pay much attention to. I share this call with the new monastics to give voice and attention to these citizens by living with them. Jesus epitomized the significance of grass-roots movements such as these. I love this principle of new monasticism! While Wilson-Hartgrove does not call every American citizen into the new monastic movement, he does emphatically state, "...The renewal of the church depends on our relocating" (86). His idea bout Sunday School classes leaving the church education wing and moving into the turf of those who are marginalized is brilliant--too bad many of these people would then have to drive 30+ minutes to get to a region of oppression. What, then? Not that I am expecting Wilson-Hartgrove to have all of these answers; I am merely asking more questions the book raised for me.

The discussion that Wilson-Hartgrove begins on page 80 is the piece in this puzzle that moves me the most. Moving into places that the Empire has rejected seems to me to not only be what Jesus modeled in who he spoke to and ate with, but even more realized in the fact that our allegiance is found in the Kingdom of God, as it was brought about by Jesus (which is why I cannot pledge my allegiance to the church). The poor, the mentally ill, the imprisoned, the handicap, the hungry, the ugly, the non-white, the immigrant, etc. live in areas of America that Capitol Hill, Wall Street, Madison Avenue, Rodeo Drive, and the Magnificent Mile do not pay much attention to. I share this call with the new monastics to give voice and attention to these citizens by living with them. Jesus epitomized the significance of grass-roots movements such as these. I love this principle of new monasticism! While Wilson-Hartgrove does not call every American citizen into the new monastic movement, he does emphatically state, "...The renewal of the church depends on our relocating" (86). His idea bout Sunday School classes leaving the church education wing and moving into the turf of those who are marginalized is brilliant--too bad many of these people would then have to drive 30+ minutes to get to a region of oppression. What, then? Not that I am expecting Wilson-Hartgrove to have all of these answers; I am merely asking more questions the book raised for me. In regards to the finance chapter, how fitting that it begins with a prayer, and not just any prayer, the Lord's Prayer. As this prayer comes at the close of the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew's Gospel, it also serves to encapsulate everything Jesus had just finished teaching. So, I find it enlightening that only in learning to pray in community "Thy kingdom come..." that an individual can then expect to share their financial resources with the entire community, taking serious the call in Acts 4:32 about a common purse and and receiving their "daily bread." In this way, the marriage metaphor that the community in Eugene, OR, Church of the Servant King uses is perfect, and also one that Wilson-Hartgrove briefly references (94). I learned from the discussion on God's abundance. Jesus is not an emissary from a scarce, simple God. Instead, Jesus represents the God who turned five loaves and two fish into enough to feed thousands, and a God who made light, and a God who sacrificed all of his son, and on and on (97). This is a beautiful image of God. How much more is God's abundant love for us? I wish our churches could preach this message more; I find it very liberating. It is, like Wilson-Hartgrove acknowledges, an economic point-of-view radically different from the world's perspective of scarcity and limited resources (98).

In regards to the finance chapter, how fitting that it begins with a prayer, and not just any prayer, the Lord's Prayer. As this prayer comes at the close of the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew's Gospel, it also serves to encapsulate everything Jesus had just finished teaching. So, I find it enlightening that only in learning to pray in community "Thy kingdom come..." that an individual can then expect to share their financial resources with the entire community, taking serious the call in Acts 4:32 about a common purse and and receiving their "daily bread." In this way, the marriage metaphor that the community in Eugene, OR, Church of the Servant King uses is perfect, and also one that Wilson-Hartgrove briefly references (94). I learned from the discussion on God's abundance. Jesus is not an emissary from a scarce, simple God. Instead, Jesus represents the God who turned five loaves and two fish into enough to feed thousands, and a God who made light, and a God who sacrificed all of his son, and on and on (97). This is a beautiful image of God. How much more is God's abundant love for us? I wish our churches could preach this message more; I find it very liberating. It is, like Wilson-Hartgrove acknowledges, an economic point-of-view radically different from the world's perspective of scarcity and limited resources (98).

No comments:

Post a Comment